A sweet stiff starter is a type of sourdough starter found in sweet bread recipes, especially sweet bread recipes where a bread pull is desired over an open crumb. But, why? How does sweet stiff starter affect bread? Let’s look at the answer to these questions, and more, below.

In this article:

- A Brief Summary of Sweet Stiff Starter

- What is sweet stiff starter?

- What is the difference between a liquid starter and a stiff starter?

- What is the difference between a stiff starter and a sweet stiff starter?

- What effect does sugar have in sweet stiff starter?

- What effect does fermentation have in sweet stiff starter?

- A breakdown of the science of sweet stiff starter

- Understanding sourdough starter to better understand sweet stiff starter

- What kind of bread should I pair with sweet stiff starter?

- Do I have to maintain a sweet stiff starter in addition to my regular starter?

- How do I make a sweet stiff starter?

- How do I know when a sweet stiff starter is ready to use?

- Do you have any recipes that feature sweet stiff starter?

- Using this concept in bread dough

- What questions do you still have about sweet stiff starters?

A Brief Summary of Sweet Stiff Starter:

- Sweet stiff starter is a low hydration starter (less than 65%) meaning it contains more flour than water. This provides more food for the yeast to feed on, which means reduced chances of your starter becoming hungry and sour.

- Sweet stiff starter contains a very specific percentage of sugar (10-15%). This is enough to create osmotic stress, which is the goal, but not so much that it kills the yeast and not so little that it actually speeds fermentation.

- The purpose of creating osmotic stress is to limit bacteria cell regeneration. This means the bacteria that create acids (sour flavor) are not producing as rapidly.

- A sweet stiff starter will only work if your process also works. Fermentation is key. Fermenting too long or cold fermenting for extended periods will still result in a sour flavor in your bread.

- This technique can be applied to your bread as well. Incorporating a sugar percentage of 10-15% can reduce the sour flavor even more without leaving a sweet taste in the bread (I do this in my bagel recipe, coming soon!)

- This starter is commonly paired with sweet breads that already contain a percentage of sugar, which works as mentioned above and helps reduce the sour flavor. Pairing this with unsweetened breads, such as a rustic loaf, may not work as well.

- Just like with anything, this type of starter may not be suitable for every type of bread. This starter is most commonly paired with sweet breads, but you are welcome to play around with it and find your perfect pairings.

What is sweet stiff starter?

A sweet stiff starter is a type of starter characterized by its lower hydration levels and the addition of sugar. Read more about dough hydration here. A sweet stiff starter contains a hydration of less than 65%, meaning it is like a dough ball and may require kneading. This “stiff” aspect of sweet stiff starter, paired with the addition of sugar, means the starter has a reduced sour taste: a desired characteristic for many in sweet recipes.

What is the difference between a liquid starter and a stiff starter?

The true definition of a liquid starter is going to depend on who you ask. For the purposes of my content, a liquid starter is classified as a starter with a hydration of 65% or greater. This is the starter that I, along with many other sourdough bakers, regularly maintain. My liquid starter is 100% hydration, meaning it is made up of equal parts flour and water by weight. It is easily stirred with a spoon and has the consistency of a thick paste. It is also easily dissolved into water and incorporated into bread dough.

To classify a starter as “stiff,” it needs to have a hydration of less than 65%. The higher proportion of flour compared to water means it cannot as easily be stirred with a spoon. Stiff starters are generally kneaded to help incorporate all the flour. When fully kneaded and lifted from the countertop, they should stick slightly. This also means they are more difficult to incorporate into bread dough, usually also requiring kneading as part of the process.

What is the difference between a stiff starter and a sweet stiff starter?

The only difference between a stiff starter and a sweet stiff starter is sugar. Only the sweet stiff starter contains a percentage of sugar.

What effect does sugar have in sweet stiff starter?

Adding a little bit of sugar to sourdough starter and bread dough can be helpful because it encourages feeding and bacterial growth. But if too much sugar is added, it can actually be harmful. This happens in sweet stiff starter. When you add about 10-15% sugar to the starter, it creates osmotic stress. This stress stops the bacteria from multiplying as rapidly, which then limits the amount of acid buildup (since the bacteria aren’t reproducing as quickly).

In other words, the percentage of sugar added is very specific. It is enough to limit the rapid multiplying of bacteria, but not enough to completely kill the yeast. Therefore, the starter still functions appropriately but the buildup of acid from the bacteria is limited, which reduces the sour flavor.

Though osmotic stress is a problem for the starter, it is a helpful effect for the baker. The buildup of acid is limited by the reduction of bacterial reproduction, so the sour taste from acid buildup is also limited. In other words, because of the osmotic stress created by the addition of sugar, overall sourness coming from the starter itself is limited.

What effect does fermentation have in sweet stiff starter?

Fermentation is a key factor to determining the effectiveness of a sweet stiff starter. A sweet stiff starter fermented for too long will use up its food source and become sour again.

Likewise, certain environmental characteristics can influence fermentation and overall sourness. A cold, slow fermentation, such as in the refrigerator, will increase the sour flavor while a quick and warm fermentation will reduce it.

I let my sweet stiff starter rise on the counter, though using a proofer would also be effective. As for the dough I add it to, a warm bulk fermentation is ideal, though using the refrigerator for about twelve hours or so will not harm the effectiveness of the starter in the dough.

A breakdown of the science of Sweet Stiff Starter:

Flour to Water Ratio:

- Sweet stiff starter is characterized by its lower hydration levels, meaning it contains less water compared to flour (by weight). The water to flour ratio determines the stiffness or thickness of the starter. In this case, the lower hydration levels result in a dough-like consistency that must be kneaded like bread rather than stirred like a thick milkshake.

- Flour is food for the wild yeast present in a sourdough starter. The increased amount of flour in a sweet stiff starter means there is more food for the wild yeast to feed on, making this starter’s feeding schedule a bit more flexible, while also increasing the production of yeast.

Acid Production:

- Stiff starters in general favor the production of acetic acid over lactic acid production, which tends to have a more “sour” flavor. While this factor alone could contribute to a more overall “sour” flavor for the sourdough starter and bread products made from it, its production is better determined by how the starter is cared for: how often it is fed, the temperature it is kept at, and the amount/type of flour used when feeding.

- Adding a sugar percentage of 10% or higher to sweet stiff starter creates osmotic stress and limits bacteria cell regeneration. This, as a result, limits the buildup of acid, discussed above, thereby contributing to a reduced “sour” flavor. (Note: Sugar not only limits bacteria cell regeneration, but also steals water from yeast. Too much sugar can thoroughly stall out yeast and bacterial reproduction, and has the potential to completely kill it. A perfect balance is necessary.)

Microbial Community Dynamics:

- Stiff starters favor yeast growth over bacterial growth, which results in a milder “sour” flavor when maintained correctly (since bacteria is responsible for the production of both lactic and acetic acid which result in “sourness”).

Fermentation:

- Fermentation is the determining factor in the overall effect of a sweet stiff starter. If left to ferment too long, or if left to ferment in certain environmental conditions (such as a refrigerator), more acetic acid will be produced, resulting in a final loaf that is “sour,” despite the use of sugar to create osmotic stress and additional flour to encourage yeast production.

Understanding sourdough starter to better understand sweet stiff starter:

A healthy starter will feed on flour, breaking down carbohydrates into sugar, which will be used to feed and nourish wild yeast and bacteria present in the starter. This creates two (really three) things.

The first byproduct is carbon dioxide, the “bubbles” that can be seen in sourdough starter. The carbon dioxide gas produced during fermentation gets trapped in the gluten matrix of the starter. This gas is what causes the starter to rise and to float when it reaches peak. It is also responsible for leavening bread and producing airiness in a loaf of sourdough.

The second byproduct is acid: lactic acid and acetic acid. These acids contribute to the “sour” flavor of sourdough bread. The production of each is determined by how a starter is cared for: how often it is fed, the temperature it is kept at, and the amount/type of flour used when feeding (as mentioned above under “Acid Production“).

Stiff starters (starters maintained at a hydration of less than 65%) are sometimes said to produce a more “sour” flavor, due to the fact that they favor the production of acetic acid over lactic acid. In reality, the effects of acetic acid completely depend upon a sourdough starter’s maintenance routine and, even more-so, on fermentation. In contrast, because of the higher flour percentage in stiff starters, yeast production is favored, which can actually result in a more mild “sour” flavor. It’s all about balance!

The addition of sugar in a sweet stiff starter limits the production of these acids even more by creating osmotic stress and limiting the bacteria’s ability to reproduce. This, in turn, also reduces the overall “sour” effect of the sourdough starter.

Overall, the low hydration of sweet stiff starter combined with the addition of sugar and proper fermentation should lead to a reduced sour effect on the final bread produced with the starter.

What kind of bread should I pair with sweet stiff starter?

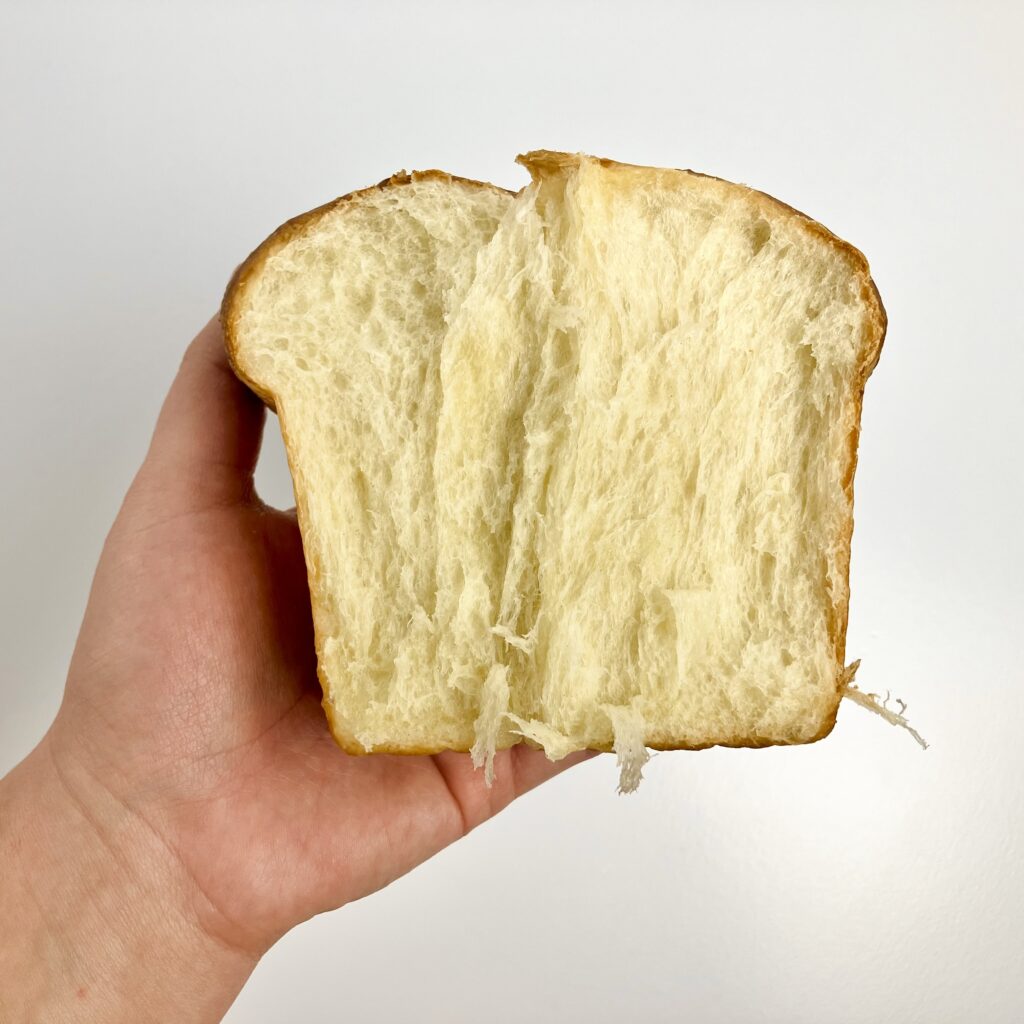

Sweet stiff starters are generally used in sweet bread recipes, where a reduced sour flavor is desired. Examples include: brioche, cinnamon rolls, hot cross buns, and donuts.

Some savory recipes also pair well with sweet stiff starter. These recipes will usually contain a percentage of sugar, though the sugar’s purpose is not necessarily for sweetness; rather, it is more-so for the purpose of creating osmotic stress in the bread dough itself, in order to virtually eliminate the sour flavor. Examples include: hamburger/hot dog buns and bagels.

A sweet stiff starter would not necessarily pair well with a wet, savory dough, such as baguettes, English muffins, or a classic rustic loaf. Though the pairing is not an abomination, it may not work well in respects to incorporating the starter and actually reducing the sour taste, since the bread dough itself does not create the ideal climate for this to work.

Overall, for best results, use a sweet stiff starter in any sweet bread recipe or in a savory bread recipe with a stiffer dough that contains a small percentage of sugar.

Do I have to maintain a sweet stiff starter in addition to my regular starter?

A sweet stiff starter can be built from your regularly maintained starter (likely a liquid starter) every time it is needed. Therefore, a sweet stiff starter does not have to be maintained.

If maintaining a sweet stiff starter is something that is desired, go for it! One fun thing about maintaining a sweet stiff starter is that the starter can be trained to become osmotolerant – meaning it can efficiently leaven bread recipes such as brioche, donuts, and some bread rolls (such as my Hawaiian roll recipe), where sugar content is high and yeast are under high osmotic concentrations.

How do I make a sweet stiff starter?

There are many ways to make and/or maintain a sweet stiff starter. Let’s discuss my basic method for a sweet stiff starter that is built off of a liquid starter:

I use a 1 : 2 : 1 : 1/4 ratio for my basic sweet stiff starter build – liquid starter : flour : water : sugar.

- 40 g 100% hydration liquid starter

- 80 g all-purpose flour

- 40 g filtered water

- 10 g sugar

The amounts here, of course, can be adjusted to fit the particular recipe that is being made. In addition, I always include a sweet stiff starter build on my recipes that use it.

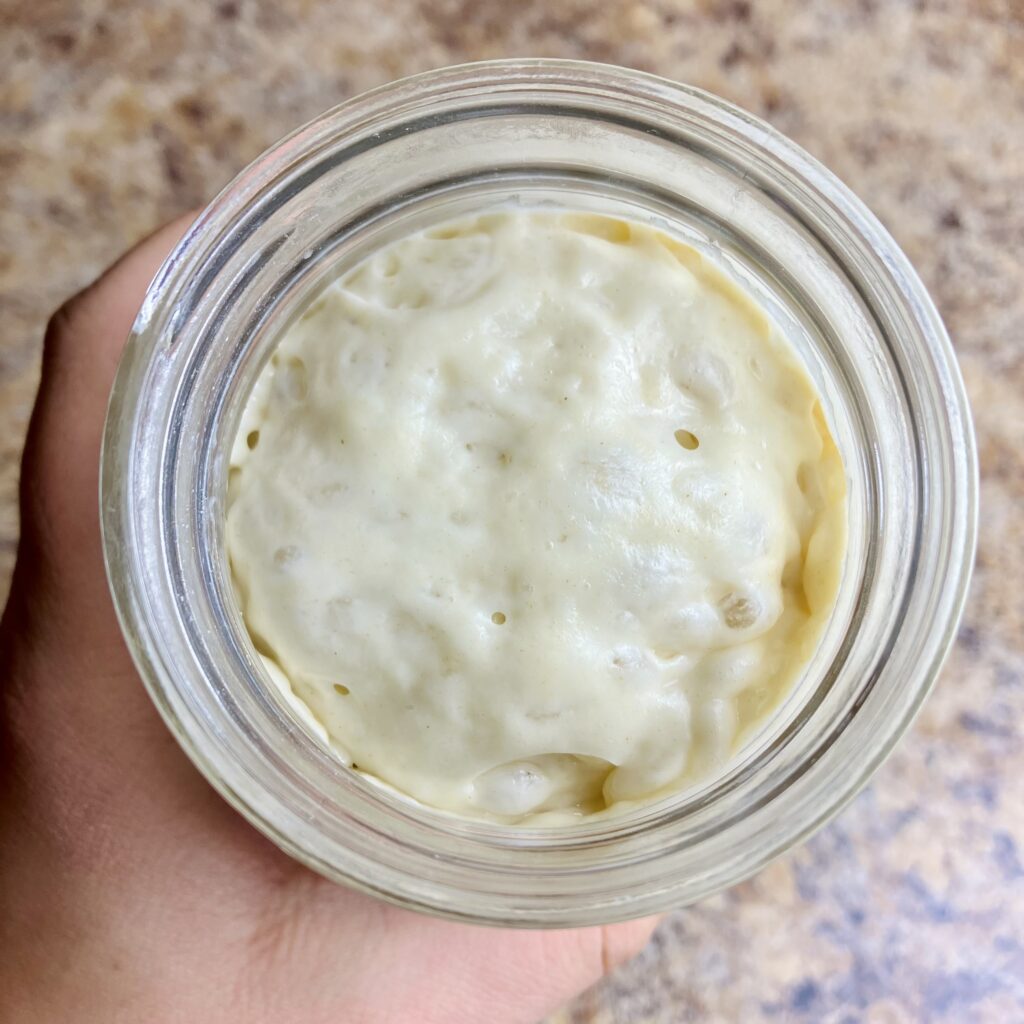

Begin by roughly mixing the ingredients together in a bowl. Using your hands, knead the mixture in the bowl or on the countertop until all of the ingredients are fully incorporated. The dough will begin to get sticky at this hydration, so use lightly wet hands as necessary. After the ingredients are fully incorporated, transfer the starter to a container to rest (covered) at room temperature for 8-12 hours before using in any sweet bread recipe.

How do I know when a sweet stiff starter is ready to use?

A sweet stiff starter is ready to use when it has doubled, or more, in size and the dome on top has slightly fallen inward. This usually occurs 8-12 hours after mixing.

Do you have any recipes that feature sweet stiff starter?

As of this moment (I will continue updating this in the future), I have six recipes that feature sweet stiff starter:

Using this concept in bread dough:

This same concept (a stiff dough, 10-15% sugar, proper fermentation) can be applied to bread dough as well! Add a sweet stiff starter to any dough containing these characteristics and you will have eliminated the sour flavor entirely.

What questions do you still have about sweet stiff starters?

Is there anything I missed when covering this information? Or, anything you are still confused about or that could be explained better? Please let me know in the comments! I’ll be happy to answer your questions and even update this article, if needed.

Happy baking!

Recent POSTS

Join the email list

Join the email list to be notified when a new recipe or blog post comes out. No spam, just sourdough. Unsubscribe at any time.

So… Is your sweet stiff sourdough recipe still contains bacteria? I mean the good bacteria it not dead right?

Yes! They are just slowed down (which is what limits or eliminates the sour flavor) but are still present to break down flour

Pingback: Tangzhong – The sourdough Baker

Pingback: POTATO ROLLS - The Sourdough Baker

Pingback: BAGELS - The Sourdough Baker

Pingback: DUTCH CRUNCH BREAD - The Sourdough Baker

Pingback: CINNAMON ROLLS - The Sourdough Baker

Pingback: HAWAIIAN ROLLS – The Sourdough Baker

Pingback: BRIOCHE – The Sourdough Baker